You are currently browsing the tag archive for the ‘tax optimization’ tag.

The steady march of technology’s ability to handle ever more complicated tasks has been a constant since the beginning of the information age in the 1950s. Initially, computers in business were used to automate simple clerical functions, but as systems have become more capable, information technology has been able to substitute for increasingly higher levels of human skill and experience. A turning point of sorts was reached in the 1990s when ERP, business intelligence and business process automation software reduced the need for middle managers. Increasingly, organizations used software to coordinate activities as well as communicate results and requirements up and down the organizational chart. Both were once the exclusive role of the middle manager. Consequently, almost every for-profit organization eliminated management layers so that today corporate structures are flatter than they once were. Technology automation also eliminated the need for administrative staff to perform routine reporting and analysis. Meanwhile, over the course of the 1990s, the cost of running the finance department measured as a percentage of sales was cut almost in half as a result of eliminating staff and because automation enabled companies to scale without adding headcount. During the last recession, companies in North America and Europe once again made deep reductions to their administrative staffs, relying on information technology to pick up the slack.

Given this history, the best career choice that an individual can make today is to stay ahead of the trend. Information technologies, especially cognitive computing, will continue to eliminate relatively high-paying white-collar jobs in corporate life, especially in the finance and accounting function. Executives and others working in tax departments in particular should recognize that a major shift is under way in their field. Automation will transform their work over the next five years, driving a fundamental change in what they do. To succeed (or even survive), they will have to embrace automation.

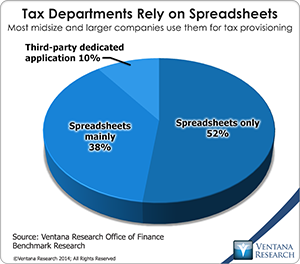

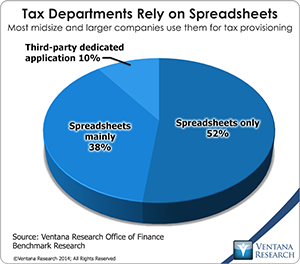

Spreadsheets are a major impediment to making the tax function more strategic for a company and more remunerative for those working in the department, as I have noted. Our Office of Finance benchmark research finds that half (52%) of tax departments use spreadsheets only for tax provisioning and another 38 percent mainly use spreadsheets; just one in 10 utilize a third-party tax application. One well-known issue with spreadsheets is that they are error-prone – not a risk that tax professionals can be comfortable with. To be certain that the tax provision and other tax-related calculations are correct, individuals must double- and even triple-check the numbers. This overlaps with a second major issue with spreadsheets: They are time-consuming. Our spreadsheet research finds that those working heavily with spreadsheets on average spend 18 hours a month (equivalent to more than two full workdays) just maintaining their most important spreadsheet. Spreadsheets as so time-consuming that they prevent individuals from doing more valuable work, in this case tax analysis and planning.

finds that half (52%) of tax departments use spreadsheets only for tax provisioning and another 38 percent mainly use spreadsheets; just one in 10 utilize a third-party tax application. One well-known issue with spreadsheets is that they are error-prone – not a risk that tax professionals can be comfortable with. To be certain that the tax provision and other tax-related calculations are correct, individuals must double- and even triple-check the numbers. This overlaps with a second major issue with spreadsheets: They are time-consuming. Our spreadsheet research finds that those working heavily with spreadsheets on average spend 18 hours a month (equivalent to more than two full workdays) just maintaining their most important spreadsheet. Spreadsheets as so time-consuming that they prevent individuals from doing more valuable work, in this case tax analysis and planning.

Another related issue is that using spreadsheets for the tax function diminishes visibility into a company’s tax provision in at least two respects. First, using them takes so long that executives get to the numbers late in the financial close process. This matters because of the impact that tax expense has on a company’s profits. Second, spreadsheets are black boxes: That is, they are difficult to control, and it’s difficult for anyone other than the spreadsheet’s owner to understand their construction. Often, assumptions are buried in formulas and therefore hard to uncover. If these formulas are inconsistent or wrong, it’s not easy to spot them. (This was an important factor behind J.P. Morgan’s multibillion dollar trading loss, which I discussed.) When a spreadsheet is constructed with a given formula repeated in multiple cells, each of these must be updated when circumstances change, and it’s difficult to be certain that all of the changes have been made. Even with advanced techniques designed to make updates consistent, it’s hard to be sure that some cell wasn’t overwritten with another number.

Some people who work intensively with spreadsheets still view them as a form of job security because of their opacity. They think they’re indispensable because they are the only one who understands how their spreadsheet works. This is one of several reasons why their use persists in functions where they constitute more of a problem than a solution. However, these spreadsheet jockeys should recognize that their tools’ inherent inefficiency, lack of visibility and proneness to error make them vulnerable to being replaced by better technology. The real value of tax professionals is not their ability to overcome spreadsheet limitations. It’s in their training in understanding income taxes. Once freed from the drudgery of performing computations, massaging data and checking (two or three times) for errors, tax professionals can turn their attention to performing analytical work aimed at optimizing a company’s tax spend – and thus ensuring their value as employees.

Midsize and larger organizations, especially those that operate in multiple direct (income) tax jurisdictions and that have an even moderately complex legal entity structure, must use dedicated software to automate their income tax provision and analysis functions. They must manage their tax-sensitized data using what I call a tax data warehouse of record. Tax departments must be able to tightly control the end-to-end process of taking numbers from source systems, constructing tax financial statements, calculating taxes owed and keeping track of cumulative amounts and other balance sheet items related to taxes. Transparency is the natural result of a having controlled process that uses a unified set of all relevant tax data. An authoritative data set makes tax department operations more efficient. As noted, reducing the time and effort to execute the tax department’s core functions frees up the time of tax professionals for more useful analysis. Having tax data and tax calculations that are immediately traceable, reproducible and permanently accessible provides company executives with greater certainty and reduces the risk of noncompliance and the attendant costs and reputation issues. Having an accurate and consistent tax data warehouse of record enables corporations and their tax departments to better execute tax planning, provisioning and compliance. Using dedicated software today rather than relying on spreadsheets helps the tax department, and those working in it, increase their strategic value today so they won’t be obsolete tomorrow.

Regards,

Robert Kugel – SVP Research

One of the issues in handling the tax function in business, especially where it involves direct (income) taxes, is the technical expertise required. At the more senior levels, practitioners must be knowledgeable about accounting and tax law. In multinational corporations, understanding differences between accounting and legal structures in various localities and their effects on tax liabilities requires more knowledge. Yet when I began to study the structures of corporate tax departments, I was struck by the scarcity of senior-level titles in them. This may reflect the low profile of the department in most companies and the tactical nature of the work it has performed. Advances in information technology have the potential to automate most of the manual tasks tax professionals perform. This increase in efficiency will enable tax departments to fill a more strategic, important role in the companies they serve.

In the past (and still in many organizations today) there was a sharp pyramid of value-added work in the tax function, with tax attorneys at the top, corporate counsel in the middle and tax practitioners at the bottom. The tax attorney, versed in the intricacies of laws and their applications – especially in cross-border situations – typically has had the greatest ability to minimize tax expenditures. The role requires a combination of inspiration and art to see the underlying logic of tax laws and legal structures to be able to apply creative interpretations to black-letter statutes and has been rewarded accordingly. Senior corporate counsel has weighty responsibilities and therefore merited elevated titles. But the role of tax preparation has been oriented toward functional execution. It typically is done hard-working experts who have limited impact on policy and decision-making. Because the workings of this group are particularly sensitive, it also has a culture that attracts people who tend to be tight-lipped and not given to self-promotion. This hierarchy has helped to keep tax matters outside of the mainstream activities of the corporation, as I have discussed.

Today, information technology can flatten the value-added pyramid by automating routine work. Doing this can give skilled practitioners in the tax department more time to spend on value-adding analysis and contingency planning because they spend less time on data gathering, data transformation and  calculations. Increased productivity creates more time to find tax or cash flow savings, as well as to provide better-informed guidance on alternative strategies. To accomplish this, corporations must automate their tax provisioning process; most will benefit from having a tax data warehouse, which I have written about. However, our recent Office of Finance research finds that this is not widely done. Instead almost all midsize and larger companies (90%) use spreadsheets exclusively or mainly to manage their tax provisioning process, including calculations and analysis, and this demands manual effort.

calculations. Increased productivity creates more time to find tax or cash flow savings, as well as to provide better-informed guidance on alternative strategies. To accomplish this, corporations must automate their tax provisioning process; most will benefit from having a tax data warehouse, which I have written about. However, our recent Office of Finance research finds that this is not widely done. Instead almost all midsize and larger companies (90%) use spreadsheets exclusively or mainly to manage their tax provisioning process, including calculations and analysis, and this demands manual effort.

Desktop spreadsheets are not well suited to any repetitive collaborative enterprise task or as a corporate data store. They are a poor choice for managing taxes because they are error-prone, lack transparency, are difficult to use for data aggregation, lack controls and have a limited ability to handle more than a few dimensions at a time. Data from corporate sources, such as ERP systems, may have to be adjusted and transformed to put this information into its proper tax context, such as performing allocations or transforming the data so that it reflects the tax-relevant legal entity structure rather than corporate management structure. Moreover, in desktop spreadsheets it is difficult to parse even moderately complex nested formulas or spot errors and inconsistencies. Pivot tables have only a limited ability to manage key dimensions (such as time, location, business unit and legal entity) in performing analyses and reporting. As a data store, spreadsheets may be inaccessible to others in the organization if they are kept on an individual’s hard drive. Spreadsheets are rarely documented well, so it is difficult for anyone other than the creator to understand their structure and formulas or their underlying assumptions. The provenance of the data in the spreadsheets may be unclear, making it difficult to understand the source of discrepancies between individual spreadsheets as well as making audits difficult. Companies are able to deal with spreadsheets’ inherent shortcomings only by spending more time than they should assembling data, making calculations, checking for errors and creating reports.

On the other hand, a tax data warehouse addresses spreadsheet issues. It is a central, dedicated repository of all of the data used in the tax provisioning process, including the minutiae of adjustments, reconciliations and true-ups. As the authoritative source, it ensures that data and formulas used for provisioning are consistent and easily audited. Since it preserves all of the data, formulas and legal entity structures exactly as they were in the tax period, it’s far easier to handle a subsequent tax audit, even several years later. In this respect a dedicated tax data warehouse has an advantage over corporate or finance department data warehouses, which are designed for general use and often are modified from one year to the next as a result of divestitures or reorganizations.

Another benefit of automating provisioning and having a tax data warehouse is that this approach provides greater visibility and transparency (at least internally) into tax-related decisions. This gives senior executives greater certainty about and control over tax matters and allows them to engage more in tax-related decisions. In companies where executives are more engaged in tax, the tax department gains visibility. Also, because automation enables better process and data control, external auditors spend less time examining the process and tax-related calculations in financial filings, and it cuts the time the tax department might need to spend in audit defense with tax authorities. Process automation enables tax departments to increase their efficiency and give members more time to apply their tax expertise to increase the business value of their work, thereby flattening the value-added pyramid.

The scope of the value that tax practitioners can add is broadening because having greater visibility into the methods used in direct tax provisioning will be increasingly important. I have noted that companies that have significant operations in multiple tax jurisdictions are likely to face a more challenging future. While I’m skeptical that there will be a massive change in how tax authorities manage cross-border tax information soon (which is more a reflection of the competence of the taxing authorities than their motivation), it’s worth assuming that it will grow at least gradually and therefore companies must be prepared to deal with increasingly better-informed tax officials. Transparency also fosters consistency in tax treatments and the ability to manage the degree of risk that CEOs, CFOs and their board are willing to take on in weighing how conservative or aggressive a corporation would like to be in how it handles taxes. This is another way for tax practitioners to increase their value and visibility in their corporation.

Forward-looking companies have been making the transition to automating their direct tax provisioning process, redefining their approach to managing taxes and giving their tax departments greater visibility. It’s unlikely that these companies are using desktop spreadsheets to any meaningful degree. It’s not clear when the mainstreaming of the tax department will be common, but it’s probably at least several years away. Evidence that a fundamental shift has occurred in how corporations manage their income tax exposure will exist when a majority of midsize and larger companies use dedicated software rather than spreadsheets for this function. That’s also likely to be when Senior Vice President – Tax becomes a common title. This promotion won’t be the result of title inflation. It will happen because the tax department’s role will be important, making a bigger, more visible contribution to the company as practitioners focus more on analyses that optimize tax decisions and far less on the calculations and other repetitive mechanical processes that consume time but produce little value.

I recommend that every CFO of a company operating in multiple tax jurisdictions with even a slightly complex legal structure consider automating tax provisioning and deploying a third-party (rather than a custom-built) tax data warehouse.

Regards,

Robert Kugel – SVP Research

Klout

Klout LinkedIn

LinkedIn Plaxo

Plaxo Twitter

Twitter Facebook Fan Page

Facebook Fan Page Facebook Group

Facebook Group Ventana Research Website

Ventana Research Website